Building D&D cities, towns, and villages is challenging. As a Dungeon Master, you either don’t spend enough time prepping a settlement to find it’s a forgettable, cookie-cutter location and one where the PCs have nothing to do and can’t find what they’re seeking. Or, you spend too much time building a city, town, or village to have the players not engage with it. So today, we’re looking at how to build practical D&D cities, villages, and all types of settlements with your players in mind. And we do that by focusing on the 5R’s of settlement design.

The 5R’s of Practical Settlement Design

You may be familiar with this concept. Every D&D group has five basic needs that a settlement needs to accommodate in the game. From the smallest pig farming hamlet to the grandest capital city, each should offer an answer to your players’ basic needs.

They need a way to report on quests and get rewards, rest & repast, shop, obtain information, and timely activities for leisure and progression (downtime).

5R’s of Building a Practical Settlement for D&D

- Rewards – Ways to turn in quests and receive rewards

- Rest – Safe locations where the characters can long rest

- Resupply – Places where PCs can turn coin and treasure into gear and supplies

- Research – Ways the PCs can learn something new (rumors, adventure hooks, quest clues, etc.)

- Recreation – Ways for PCs to relax, have fun, and work on downtime activities

Often GMs will get bitten by the worldbuilding bug and spend a lot of time prepping settlement details that aren’t important to the functions needed to serve their players. I’m very susceptible to this as well.

But now, when I prep locations for my D&D sessions, I try to first focus on addressing these points. Afterward, I’ll do a little worldbuilding and fleshing out a location more if I have time.

1. Rewards: How to Finish The Current Quest

The classic D&D quest includes a quest giver or adventure patron that summons the party and lays out their mission and reward.

That sounds pretty simple, then. Go back to the adventure patron and collect the reward, right? Well, yes and no. Most adventures in Dungeons & Dragons are location-based adventures, so the party will usually travel many days to reach the adventure location.

Consider WoTC’s Tomb of Annihilation. Set on the continent of Chuult, the PCs must cross an ocean from quest giver to quest location with all the action.

You could have the players return to their patron afterward, but that’s a lot of travel. What happens if the players really like Chuult with its zombie-infested dinosaur jungles, and you want to run some more adventures in the location?

Well, D&D players aren’t going to miss out on their payday. As much fun as Chuult is, they will be sailing back to collect their reward. Instead, consider how they can complete the quest without schlepping halfway around the world just to collect payment.

Think about including a messenger service or having a representative for the adventure patron show up to check on the group’s status. The representative can reward them right then. Or they can go on more adventures in the area or enjoy some downtime while they await their letter to reach the patron and their reward to be sent over.

Of course, any adventures they run down in the interim will need a way to finish the quest once back in town.

Faction and organization holdings are an excellent way to make this easy. Having adventurer guild branches dotted around your setting makes it easy for quests to be turned in for rewards and provides easy access to adventurer goods and services like having a place to eat and sleep. That leads us into the second R, Rest.

2. Rest: Places to Eat, Drink, and Sleep in a Settlement

This R can be a surprisingly sticky subject for smaller locations. But, first let’s talk about making the most of it in a big settlement.

Food is accessible in a big city. The key is to offer variety to make it engaging for players. Talk about the street food available in the market stalls. Make a note of kitchens that serve hearty, inexpensive fare to the everyday worker offering only one or two daily dishes focused around lunch. And, don’t forget the classic tavern offering pottage, catch of the day, or cold antipasti/charcuterie boards.

Adventuring parties tend to turtle up in the inn until they get hit with the next story beat. The problem is most D&D inns are boilerplate, carbon copies, so they’re pretty forgettable.

The idea with the Rest ‘R’ is to broaden your group’s horizon and increase the number of locations and interactions they encounter in a settlement. Doing this helps your locations feel alive and encourages players to do more roleplay with NPCs and within the party.

Better D&D Games by Removing Inns

You can also do this by taking away the archetypal, all-in-one inn. I align closely with Domesday Book information in Medieval Demographics Made Easy, which I suggest every medieval fantasy game master read.

According to the historical data, there’s an average of one inn in a settlement for every 2,000 residents. So most villages and smaller settlements won’t support an inn. Now we have to think of where the party can eat, drink, and sleep in these small settlements. Even the typical tavern averages one to every 400 residents.

The party could always rough it, camping outside a small village and relying on their travel rations to get by. Or, as was most common, they could negotiate with one of the villagers to put them up for the night.

The local lord, priest, or reeve could have a bedroom available for the adventurers, or they could stay in a farmer’s barn in exchange for coin or the latest news and stories from their travels. Or, in the direst circumstances, lodging in exchange for their labor. Hospitality in this fashion would likely include a portion of the meal the family cooks.

A Brief History of Pubs for Verisimilitude

Now is a good time to bring up alehouses. In ye olde times, beer was brewed at home. Once ready, the family would hang a branch over their door to signal to people they had beer available. People could then purchase the homemade ale.

A communal activity where people might set benches out front to enjoy the beer without being in a cramped house. Not too difficult to see how this transitioned into German bier gartens.

These homegrown enterprises would later go legitimate and become public houses, “pubs” as we know them today. These public houses were differentiated from private residences and were available for the general public to use, and were places where business was conducted.

Understanding the Difference between Alehouses, Taverns, and Inns

Between history and pop culture, the differences between these establishments can be murky, especially if you’re an American. An alehouse is a place that serves beer primarily. Like a wine bar, the categorical name is pretty accurate. If it’s a business open to the general public, it’s a pub (public house).

Alehouses and taverns are the local entertainment. They often offer music, gambling, and more to the same locals daily. It’s the neighborhood bar where everybody knows your name. Think Cheers!

Alehouses Versus Taverns

Initially, the difference between an alehouse and a tavern was the latter focused on serving wine instead of ale. But, over time, it became a way to identify the precursor to the modern restaurant. It’s a business that serves food and drinks.

Now, for a bit more confusion. Taverns sometimes allowed overnight lodgers to sleep in the main room in a hostel-like situation. But, this required an amount of trust between the proprietor and lodger.

Travelers were not likely to be trusted on their word alone, so if the tavern keeper didn’t know who you were, they might not let you stay. It’s why documentation was worthwhile. If you were a pilgrim and showed the master your travel letter signed by the archbishop, your chances of acquiring lodging improved greatly.

Taverns Versus Inns

Essentially, inns are taverns with rooms for rent. Most rooms were not private and you would be sharing a large bed with perhaps four or more people. But, it’s better than sleeping on a pub floor that smells of stale beer.

Traveling Adventurers, Lodging, and Stranger Danger

Here’s an interesting tidbit about pre-industrial cities. Even large cities were very community-focused. As noted above, for most places: stranger = danger.

So cities would check people coming through the gates. Who are you, nature of your business, length of stay, AND (what’s dropped from that list in popular media) where are you staying/who can vouch for you?

Hosting Travelers and Liability

To avoid vagrancy and reduce criminal activity, a visitor needed to provide someone who could vouch for them and offer them lodging before gaining entry to the city. Basically, a city resident and community member must take on legal responsibility for the actions of you, an outsider and stranger, while you’re in the city.

Innkeepers would provide this service to merchants, pilgrims, and other travelers. This service means an innkeeper assumes A LOT of liability by renting rooms to strangers.

Most Inns Would Hate D&D Adventurers

Now imagine the typical D&D adventuring party and their hijinks. What innkeeper in their right mind would take on that liability?! Again, having letters of introduction and other documentation of who you are and that you are good people opens many opportunities.

Letters, references, and official documentation are fantastic, non-monetary reward ideas for adventuring that you should add to your game.

How to Make a D&D Inn Interesting

The bottom line is whatever the adventurers do while in a settlement, the innkeeper is legally on the hook. It can be a great way to hold PCs back from flagrantly lying, cheating, stealing, and stabbing their way through problems. They can see the innkeeper paying off huge fines or being shackled and dragged through the streets for their trespasses.

It’s the perfect way to occasionally saddle players with an annoying NPC that’s keeping tabs on them for the innkeeper. The perfect wrinkle if they’re attempting some clandestine operation and acting all sorts of dodgy.

Dungeon Master Note

Remember, as DMs, we’re not trying to railroad the players into a specific type of behavior or style of play. We just want to place obstacles in the players’ way and present thoughtful choices for them to make.

Player Characters Act, the World Reacts

The innkeeper will have the city watch on metaphorical speed dial to keep the adventurers out of trouble and in line. An example of this in popular media is Turn: Washington’s Spies. While the show is middling, the main character does stay in a city inn as part of his spying and is nearly exposed through observation by the inn’s suspicious staff.

Improve Your D&D with Alternative Lodgings to the Classic Inn

Consider alternatives to the traditional inn. Dormitories, boarding houses, medieval-style hospitals, and private homes with room for rent are all great lodging options to help you shake up your playing.

If you plan to have your D&D party stick around in the city for a while, consider offering more permanent lodging through apartments and rental properties. That will give them semi-permanent neighbors to grow relationships, especially if all the PCs are lodging in different locations.

3. Resupply in a Settlement

Most players and DMs have a love/hate relationship with town time and shopping. For better or worse, the explosive success of D&D live streams has shifted the paradigm regarding in-game shopping.

Some of the most entertaining and fan-favorite moments in shows like Critical Role come from doing in-character roleplay of errands, shopping, resupplying, and goofing off around town in between adventures. So then comes the expectation that Dungeon Masters provide a space for these moments of levity and character-building between dungeon delving and monster slaying.

What Goods & Services to Offer Adventurers

What does your settlement need to offer for goods and services to the average D&D party? First, services the party needs to reach and complete an adventure. Offer guides, hirelings, mounts, spell casters, and other NPCs to help the party.

Big adventuring parties stocked with retainers were a big part of old-school D&D and OSR clones. However, the human resource management of the game has been de-emphasized in modern editions in favor of smaller adventuring party rosters with more capable heroes.

Retainers to Round Out an Unbalanced Adventuring Party

Thanks to the sidekicks content from Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything, Dungeon Masters can offer players a lot of flexibility outside the standard party composition. Hiring and running useful NPCs to serve as fighters, thieves, and magical experts is much easier now. Meaning you can provide a wider variety of quests to your players and recurring NPCs players can grow to love and hate.

Selling Treasure & Spending Coin in Settlements

The second core concept when it comes to shopping is offloading treasure. Whether it’s a scroll of Entangle no one in the party can use or an ornate jewelry box, PCs like to travel light and exchange anything that’s not useful to their adventuring for cold hard cash and coin to buy things they can use.

Don’t Skip the Shopping RP if Your Players Like It

If you have players who are really into town-time roleplaying, make sure they have to jump through hoops to sell off their treasure. For instance, a jeweler would be interested in the ornate jewelry box but not so much in a spell scroll.

Again, our fundamental role as Dungeon Master is to create engaging obstacles for our players to overcome.

Finding the right buyer and negotiating the sale of plundered treasure is catnip for some players. But, it’s about knowing your specific group of friends.

Know Your Players and What They Like

If you have a group of Slayers and Power Gamers who would find the above extremely tedious, let them lump together all their treasure and sell it with a single negotiating roll for price. The more days they are willing to spend running around town to find the right buyer lowers their sale price negotiation DC. Simple, effective resupplying that gets your players back to the part of D&D they like best.

Delay Offloading Treasure

I use 10% of the settlement population as a rule of thumb for the settlement’s Buying Power (BP) in gold pieces. Maybe that ornate jewelry box is worth approximately 250 GP. That means the party can’t just stop at the next hamlet and sell it at full price. They must visit a settlement with a population of 2,500 or more people to find a ready buyer for the jewelry box at its fair market worth.

Denying immediate exchange of treasure does two big things for your game. First, it gives the characters an in-game reason to trek to different settlements. Maybe the closest settlement to offload the jewelry box is five days away. Do you spend a week and a half going there and back to sell one treasure or hold onto it until you hit the next significant settlement?

Not All Treasure is Created Equal

The second thing it does is make the players consider what treasure in a dungeon is worth taking. An ornate jewelry box is pretty easy to transport, but what if it was an ornate rug or tapestry? Now two characters have to lug this heavy textile around and hope it doesn’t get soiled or damaged by weather or travel. Maybe your players decide that sounds like a pain in the butt and leave it behind.

This is why I very rarely give out magic storage items like a bag of holding in my games.

That is, players making the choice to leave treasure behind in a dungeon.

It is hard to emphasize how big a game changer can be for your campaign, especially when managing PC wealth accumulation. But maybe those hirelings with the wagon in town the players blew off starts to seem like a huge regret.

The third point for player shopping needs in your settlements is upgrading gear and resupplying consumable resources. Again, for the right type of player, you want to expand this section of your games. Rather than a one-stop outfitter, the party needs to visit several different shops and market stalls to cobble together homemade travel rations.

Nothing Off-the-Shelf

Most D&D worlds are artisan-driven. They don’t have the economies of scale and mass production we enjoy. Instead, most items should be made-to-order. Expanding the time your players need to stay in a settlement helps them engage with the setting and allows you to slowly chip away at their accumulated wealth through daily costs.

Everything from healing potions to swords takes time and resources to create. By the book, it takes a day to create a basic healing potion in D&D 5e. So if the party wants to stock up, that means waiting a number of days in town equal to the number of potions they want to buy or make themselves.

Make It Worth the Wait

Now, the trade-off is you want to make key items unique and special. Have the player describe the sword they forged: what inscription or mark is stamped into the blade? Make these essential mundane and magic items unique because they’re tailor-made for the PC.

Now, this can put them in an interesting position when they find a +1 sword later on and have feelings of trepidation to swap it out for their unique sword. This ambivalence can lead to a small side quest where the players can find someone or figure out how to transfer the enchantment from the new sword to their personal sword.

4. Research in a Settlement

Much of what we’ve discussed is focused on making settlements a little more unique and complex, plus making activities take longer than the average D&D game.

Give Players Something To Do in Town

In my 15+ years of playing and running D&D, town-time is only boring when the players feel like they have no direction or nothing to do while there. Waiting five days to get armor repaired is by itself dull.

The fourth and fifth R’s focus on creating better, player-focused settlements by providing players with things to do in a settlement.

Job Hunting in a Settlement

Often in D&D, we throw plot hooks at the players hoping they’ll take the bait. But spending time in town after wrapping up an adventure is the perfect time for the party to seek out new work.

And that doesn’t have to be a straightforward D&D adventure. For example, the local thieves guild could use the party’s rogue as backup for a heist. Regardless of success or failure, you can hit the party with some consequences for the rogue’s actions.

Some of the party may be able to journeyman with skills earned in their background to help cover the cost of their stay. These don’t have to be one-and-done experiences either. Maybe the party’s cook is helping out in a kitchen where they get the opportunity to meet with an important NPC who may call on them later. These small adventures, personal work, and even the act of job hunting should be treated as jumping-off points for new scenes and encounters. They are opportunities to do more and provide your players with options to go after the sort of gameplay that sounds most fun to them.

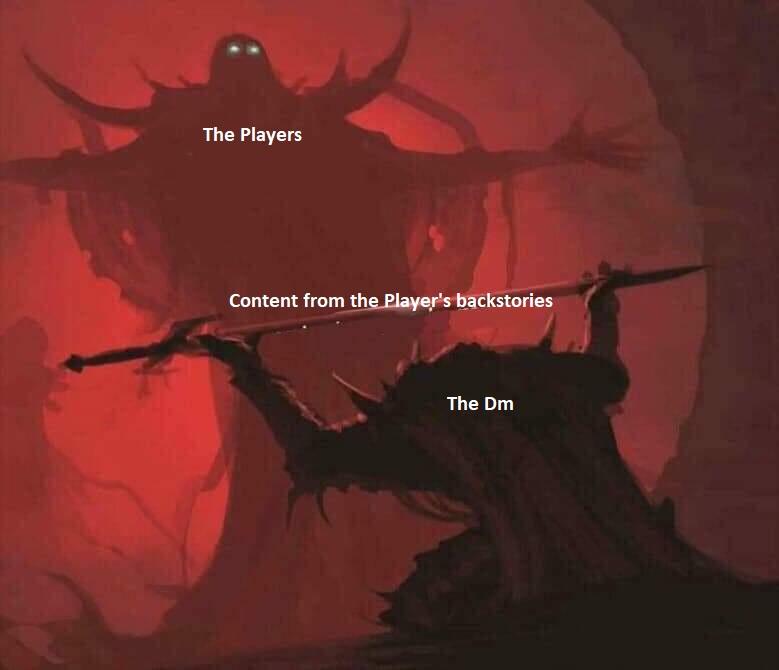

Factions, Family, and Friends

Where the last bit was about discovering something new, this is about bringing back your player characters’ history. Settlements offer the perfect opportunity to connect with the notable people and organizations of the party’s adventuring career and individual backstories, like the thieves guild from above, including factions in your settlements for your different PCs. Most settlements have some religious establishment for clerics and paladins to visit. It’s not hard either to provide a local druid or forester for the outdoorsy types.

Bring back NPCs from previous adventures who are now living or traveling through the location. Have a PC’s sibling track them down, receive a letter from home, or a care package from grandma complete with an itchy handmade sweater.

Sometimes players will proactively go out to make these interactions happen, and other times you want to pull them into it by peppering these opportunities throughout your campaign. They help the world feel like it’s alive and remind the PCs of their actions’ rewards and consequences.

Most importantly, though, have an opportunity or an obligation tied to these NPCs. Give players something to do in town.

Doing so will help you avoid the situation where the cleric shows up at the local temple and says, “hi, I’m in town,” and that’s the end of the scene. Maybe the temple priest is an old classmate from acolyte training that invites them to dinner to pick the PC’s brain about faith and the responsibility of wielding divine power.

These things don’t have to be laid out meticulously in your prep. Just remember to try and add meat to the bones, so the player’s choice to do something in town feels like it matters. For instance, the player of the cleric above would realize that if they hadn’t decided to check in at the local temple, they wouldn’t have seen their old friend and had a lovely evening catching up and swapping stories.

News & Rumors for Your D&D Campaign

News and rumors aren’t just for dropping adventure hooks. While that’s common fodder for settlements, you can do much more with them. Use your news and rumors to sprinkle in foreshadowing and wild goose chases. Help the players learn about things happening in the world beyond their immediate area. It’s not an adventure hook for right now, but it puts them on notice for a potential adventure in their future.

You Can’t Trust Everything You Hear

Sounds silly to say, but make sure some rumors are false. If they decide to go on a wild goose chase for buried treasure after talking to the town drunk, that’s on them. Let them waste time and resources looking for something that doesn’t exist rather than make it exist.

You may think your players will get upset with you, but they will not. They will get upset at the NPC and at themselves for taking the drunkard seriously.

Make in-character communication unreliable. More than lie, people make mistakes, misinterpret things, forget points, and just plain don’t know what they’re talking about. Your NPCs should too.

Sure they’ll be disappointed, but after coming back angry and cuffing the town drunk while the locals laugh at them for their fool’s errand, they’ll have a fun story to tell about your game. It helps reinforce that random NPCs are unreliable narrators on behalf of the DM. Whether intentional or not, NPCs should deliver inaccurate information to the party when it makes sense.

The village doesn’t know what’s making everyone sick? Probably loose morals inviting demons into the community. You may have eye-rolled at that, but have a random NPC tell the adventuring party demons are poisoning the village, and they’re liable to 100% believe it.

Use that to your advantage, not to make your players feel small, but so they understand there’s no substitute for critically assessing a situation for themselves. Certainly not the demonology expertise of a local turnip farmer.

Quest Research in Any Settlement

Through this section, we’ve been assuming that the adventuring party is between adventures and looking for new work. But that’s not always the case.

Since most D&D adventures are location-based, travel is integral to their success. Not just travel to and from the quest giver and adventure site, but also in the middle of the dungeon.

While rarer in modern D&D editions, there are plenty of reasons a party might want to leave the adventure site and travel to the nearest town mid-adventure.

One reason is to resupply. Another common cause for returning to town is to research part of the adventure the player characters haven’t been able to figure out.

Sometimes the Party Needs Help Getting Unstuck

But, your players can only do that if you provide research resources for them to use in the settlement. That shouldn’t mean you put a collegiate library in every settlement, regardless of size.

You should, however, include some meager ability to research, even in a tiny hamlet. Quantity of information is important, but just like the preceding section touched upon, so is fidelity.

The closest settlement should offer the best source of local area knowledge. And for D&D, asking one of the local village elders about a subject should function as the Researcher trait from 5e’s sage background.

Sure, the local turnip farmer can tell you about the local area where his family has lived for generations, but he’s not going to be much help about dungeon-specifics. You have to ask the right question to the right person.

I remember a Time Team episode where the archaeologists are trying to find evidence of an old wall surrounding a cloister. They look at old maps, surveys, aerial photos, and ground radar to no avail. Finally, they ask the farmer who lives nearby and knows exactly where part of the wall is still standing and takes them straight to it.

That’s when you begin to daisy chain information. Maybe the farmer did have someone from the nearest university show up last year asking similar questions. Simple then, the players will need to determine if they want to try to go forth blindly or take the time to go out of their way and track down this university scholar.

It’s a balance of not over or under-providing help that doesn’t make sense for the settlement. You want to create a path for the party to get the information they’re looking to find, even if that means impregnating the current adventure with a small side quest to track down a university researcher.

5. Recreation in D&D Settlements

One of the modern D&D isn’t very good at is pacing, especially regarding player character power. According to `the DMG, you should reach levels two and three after about 8 hours of play each. And for levels 4+ every 16 hours of play. But, in-character time, characters can go from being no-name scrubs to powerful and comparatively wealthy local legends in a matter of days.

Downtime is a powerful DM tool and can be a lot of fun for most players. The slayer and power gaming archetypes can get bummed if you don’t remember to mix in some action during it. As a tool downtime activities do two critical things. First, they slow the break-neck pace of in-character power progression. Second, they give your players a reason to consistently spend money, if only a little.

That’s not to say that downtime takes a break from the game or its narrative. Players can still progress during downtime if that’s what they choose to pursue, such as building a stronghold.

Building a Stronghold

A great reward to add to your game is a deed of ownership. It could be a rundown tavern in the city or a piece of virgin land for the party to do with what they want. Creating a home base of operations is a lot of fun for players and has been a staple of Dungeons & Dragons since the beginning. Your players get to make their stronghold however they want, so long as they can pay the costs and stick around to see it through.

It’s also a great way to discourage the usual murder hobo behavior as the affected can always make a reprisal on the party’s home base. If you’re more interested in the carrot than the stick, a home stronghold is a fine way to anchor your players in a specific part of your campaign world and entreat them to care more about the what’s happening in the locale and its well-being.

When adding a stronghold as an opportunity in your campaign consider offering a handful of different options. Maybe they can take up a dingy dockside tavern, a craftsman shop, or a nearby countryside hall. Each offers the players different locations and ways they can use the property. This option can be especially important if your players want to turn their base into a revenue-generating location.

Item Crafting

The company line for D&D 5e is that magic items are not readily available for purchase by player characters. With the exception being consumable items like healing potions and spell scrolls. A Dungeon Master need look no further than WoTC’s vague and broad pricing parameters for magic items, with the only differentiator being the item’s rarity.

So assuming you are playing closer to the rules as written and intended by the official game designers, most items need to be found or made by player characters. Therefore it’s crucial when creating your settlements to consider their desire to craft items. Even a tiny hamlet should have someone familiar with basic medicinal arts who can at least sell or instruct the PCs on how to find local resources to craft something like a healing potion.

Larger settlements should provide access to the high-quality inks and vellum to craft a spell scroll. Some settlements may have a full-blown magic shop or temple with a corresponding magic user who can help the players find resources and assist them in crafting items.

I believe that the design intent for magic items in 5e was for adventuring parties to go adventuring for magic items. The subject is briefly mentioned in multiple sourcebooks, but never explicitly pushed as the intended mode of play. So instead of plumbing an ancient ruin for a magic weapon, you can create rumors and adventure hooks for your players by giving them semi-exotic materials needed to craft permanent magic items.

Want a magic weapon? The steel must be quenched in the blood of a dragon. Are you looking for a new wand? Well, powerful wands are said to be carved from basilisk bones.

And, it’s vital to remember 5e’s official magic items are pretty limited. Don’t be hesitant to homebrew magic items, especially consumables. Along with hired-gun sidekicks, having ready access to one-time magic items can help keep your party balanced without pushing a player towards playing a specific role, like the healer. Items like “smelling salts of revivification” can be expensive (helping to keep wealth bloat down) while ensuring a character that gets dropped to zero can get back in the fight without a divine caster in the party.

Now, remember the scale of what can be bought and sold in different sizes of settlements. The local pig farming community shouldn’t have keen insight on where the party can obtain angel hairs to create their holy avenger. So treat crafting materials in the same way as quest research. Pig farmers may not know anything about celestials, but they should be able to point the target in the direction of the closest major religious temple. A major temple is likely to be a good source of information on where they can track down angel hairs.

The final piece to consider when determining how a settlement supports item crafting is its facilities. Can the item be created here, and at what cost? Crafting items in D&D 5e can take weeks, even months to complete and that’s assuming the party has the resources and facilities to craft. That is a lot of time to pay for daily room & board if they don’t have a stronghold. And I think it’s reasonable to assume creating permanent magical items requires specific tools and equipment, which probably also needs to be rented or otherwise accessed—another fine opportunity for a small side quest for the local mad artificer or gnome tinkerer.

Leisure

You may have noticed a trend by now. Most downtime activities take a lot of time. At the same time, many party members may have something specific they want to work on, personal missions, and goals they’re pursuing. It’s quite likely you may have a few players who have nothing to pursue in a specific settlement. That’s why it’s essential to have some leisure activities/encounters available to keep these players interested during downtime.

Providing leisure also helps you manage the tension and thus the pace of your campaign as a Dungeon Master. Small and silly leisure activities help release tension and provide some well-earned levity for your group. The DMG and Xanathar’s Guide to Everything are good places to start. You can reference their downtime activities sections with particular attention paid to the carousing information.

And that’s where a lot of Dungeon Masters stop. If you really want to create a fun and memorable time for your players in between adventures, you only need to answer one question:

“What do the townsfolk do for fun?”

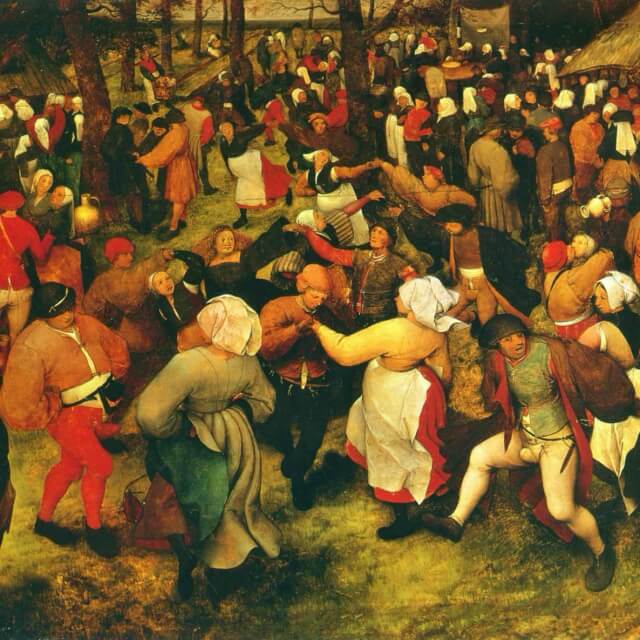

Consider the people who live in your settlement and consider what they do for entertainment and how they spend their leisure time. Pints at the pub is an ordinary relaxing evening, but not everyone does that every day. They will play games and sports, perform, dance, read, throw parties, and more. Maybe they have song, poetry, or storytelling competitions. People host dances and race animals.

And rather than doing an ability check with a die roll to participate in games, play the game itself. Draughts (checkers), Chess, Othello, card and dice games are all excellent options. Here’s a simple, authentic medieval/renaissance gambling dice game that you can teach in a minute.

In my last campaign, I included an athletics competition by the local combat school/dojo to seek out recruits and for students to test out what they’ve learned. There was a combat ring, an archery/handaxe throwing range, and a footrace with contestants sprinting, climbing, contorting, balancing, and jumping through obstacles across the town. And I introduced the event on the previous day the party was in town by having many eager contestants hitting the shrine to pray for success.

Also, consider holidays, observances, rituals, and rites. It’s common for a D&D party to participate in a carnival or a prominent religious celebration in a campaign, but when was the last time they visited a town to find two people getting married or someone celebrating a birthday? Invite them to witness or participate in a coming-of-age ceremony, maybe something like a quinceañera or debutante ball. Or have them drawn to the sounds of a New Orleans-style jazz funeral marching down the road.

All are great ways to give your players something to do in town while getting them involved with local NPCs and allowing you to share your worldbuilding.

Training

Training is the last downtime activity your players may want to participate in while in a settlement. Again, the 5e DMG and XGE books pretty well cover this aspect of downtime. What you need to know about training in D&D 5e is that it’s expensive (250 GP) and it takes a long time (250 days). Your mileage may vary, but most campaigns don’t have 8-9 months of sitting around. So doing training to gain a new proficiency is unlikely. You and your players need to commit because your training is most likely to be successful if it’s done a few days or weeks over the course of the campaign and in-character years.

Still, it is something that players can be interested in pursuing. Well, to learn, they will need an instructor. Often, player characters will turn to the others in their party for instruction. It makes more sense for a D&D character than a typical teacher. They will be with their party most days, often all day. It’s easy to imagine how walking down a trail to the next dungeon offers plenty of time for one PC to teach another conversational Orcish.

Training becomes a bit more complicated when no one in the party has the proficiency the player is seeking. For example, in the current adventure, the party is tracking down ancient magical artifacts and trying to decipher what they do. If the party doesn’t have someone trained in Arcana, they probably want to rectify that. But, that means staying in town for 250 days so one character can get the proficiency to make life easier for them. It kind of deflates the stakes and urgency of your campaign. Assuming they’re in a farming village, they’ll need to travel elsewhere to find an instructor.

This opportunity is the perfect place to have a skilled hireling for the party to find. The hireling could be a wizard’s apprentice or a veteran adventurer who lost their previous party. This person will need to be paid and outfitted by the party if they plan on taking this person on the road.

Hirelings may be helpful in combat or not. The sidekick could just be a walking-talking proficiency bonus. Or, the sidekick can have their own agenda and foibles.

Maybe a wizard’s apprentice is not wise in the ways of the adventurer and is very likely to lead the party into ambushes, set off traps, or get themselves captured by enemies. The veteran adventurer may need much convincing to go out with a party of green foots. The adventurer may constantly disagree with the party on what they should do and how to do things, making them a real pain in the butt. Or, perhaps the veteran adventurer has eyes on the same magical artifact and is waiting for an opportunity to put the PCs in a bind so they can make off with the artifact to follow their own adventures.

You could also just make learning a proficiency something a person can do from a book. Maybe the book costs twice as much but can be taken anywhere. Without an instructor, you may decide to make learning proficiency a long-term skill challenge. Perhaps the PC can make the affiliated d20 roll once per week and keep a sum of the check results. Once the check results meet or surpass 500, they’ve gained proficiency. This is also nice to allow multiple characters to learn proficiency by passing the book to another party member once finished.

Closing Notes on 5R Settlement Design for Dungeon Masters

Whether your prepping for your next D&D game or need to improvise a village, town, or city in your D&D session, focusing on the 5R’s will help ensure the location you create is helpful for your players. And the 5R’s provide plenty of charm and originality to make your location fun and memorable.

Pingback: How to Solo RPG with Dungeons & Dragons - Red Ragged Fiend