Why should you make a D&D campaign primer for your homebrew setting and games? A primer helps make clear the most fundamental parts of your campaign for your players and pre-emptively answers the most common players questions. In a way it serves as both an outline for your upcoming campaign and a player FAQ.

A good D&D campaign primer informs players of the campaign’s setting, its overarching genre, and the tone you’re trying to exude. A good primer provides information about the characters within the campaign, both NPC and PCs, and provides your players with the Do’s and Don’ts of character creation to ensure the PC they bring to the table will immediately fit into the game.

But, a campaign primer isn’t just for the beginning of a campaign. A great primer will have information that’s useful throughout the campaign, providing information and serving as a reference for the most basic information about your table, campaign, and setting. Let’s talk about some of the best practices for creating a campaign primer.

Campaign Primer Creation Best Practices

First and foremost a campaign primer is a resource for your players. So, we want players to actually read and reference the campaign primer so we need to focus all the information around three core values.

Make your D&D campaign primer relevant, useful, and concise for your players.

Focus on providing information in your primer that’s especially relevant to the start of your campaign, the first few sessions. To sit down at the first session of a new campaign players don’t need to know about the Dawn War from a millennia ago or the name of the dwarf empress on the other side of the world.

Your players need to know information about the starting location, the initial adventure, and basic world information that affects the average person living in the area. If goblins are a known nuisance in the area, it’s plausible the PCs would know that and when they find a dead body on the road they would easily assume the cause to be goblins until proven otherwise.

Additional info that’s relevant and useful to your players would include player expectations, character creation guidelines, a crib of your house rules, and the safety tools you use at the table. To make this information concise and easy to reference include lists, tables, and a strong document hierarchy of sections and headings for fast skimming.

Make your D&D campaign primer evocative.

In addition to the core values of relevant, useful, and concise, a great campaign primer excites players. It should get them itchy to create a character, play in your game, and explore the setting.

Avoid Metachlorians

It’s OK not to write out every fact and minute detail of your upcoming campaign. Like metachlorians, explaining something can hurt your player’s excitement and buy-in. Use mystery to your advantage in a campaign primer. Tease your players with just enough information to pique their curiosity and leave them with more questions about the upcoming game than answers.

That resulting curiosity is what hooks players. They should want to know more about something specific in the world you hinted at in the primer or get excited to visit that one cool location you mentioned.

Make sure your primer’s information is up-to-date.

This issue is less of a problem if it’s your first time creating a D&D campaign primer. You should still review updated information and errata about the rules systems, monsters, and character options available to players.

Where this most often comes into play is when you’re creating subsequent campaign primers. It’s not uncommon to pick up an old primer and tweak it to create the primer for your next D&D campaign, as much of the information will be similar. Especially if you’re running multiple campaigns in the same world setting.

Just be diligent in checking the information. If you’ve change what safety tools you’re using, have made changes to the homebrew rules and resources available, or something has changed in the campaign setting, those details need to be updated so players are operating from correct information.

Also make sure to include changes for a different genre you want to emulate or game tone. You may still love your horror setting, but want the new game to be more like a slasher flick and less cosmic horror.

What to do when a player asks a question about your setting you haven’t prepared?

When using a D&D campaign primer you will inevitably be confronted with this issue. At some point your player is going to have a question you don’t have an answer for. That’s OK, this isn’t a school exam. If you don’t know the answer off the top of your head or need to think about the answer and what it means for your campaign, tell them you need to check and will get back to them on it.

Alternatively, you can open the doors and make it a collaborative process with that player. Working together with your players will improve their buy-in to the campaign because they have a vested interest in the game and its success. Even if it’s just a little piece, the game now has their thumbprint on it.

It’s well worth it to look for opportunities to collaborate with players on the creation of your campaign. Even if you don’t love their additions, you can consider it non-canonical and ensure it won’t persist outside the current campaign. This type of disclaimer can be useful because you often won’t know about the impact of player additions and changes until the campaign is already underway. It provides an out later in case the player tweak doesn’t work well.

Expect Less-than-Perfect Player Response to Your Campaign Primer

There are few things in this world that make most people drop whatever their doing. I’m willing to go out on a limb and say that a D&D campaign primer isn’t one of those rare instances. The reason we keep hammering that brevity and usefulness is so important is that the audience for your campaign primer, your players, are busy people.

As a DM, your game is your baby and you spend exponentially more time thinking and working on what goes into it to make it the best game possible than your players. Even the most dedicated player’s efforts will always pale in comparison to your own. So I wanted to provide the bell curve of player responses to a campaign primer.

Bell Curve of D&D Campaign Primer Responses

- 5% – Already have chosen a character to play regardless of the campaign

- 20% – Say they will review it later and forget

- 50% – Skim it while making a character and never look at it again

- 20% – Misinterpret a core conceit of the character they make

- 5% – Will learn it by heart and make it gospel for their character and the game

If you keep this distribution in mind, you will have more realistic expectations to the level of your player’s response. Of course, with many new games you run you may have a player who wants to play something outside the boundaries of what you set up for the campaign.

What to do when a player wants to play a character that doesn’t fit the campaign (setting, genre, tone)

A player comes to you with a character idea that doesn’t quite fit with your idea for the upcoming campaign. It may not fit the setting, the genre, or the tone that you’re attempting to create. Your first order of business is to determine why they want to play this specific character.

It could be as simple as a mechanical choice: they want to play a Tiefling so they can gain resistance to fire damage. These are the simplest issues to circumvent with a little bit of homebrew. You can let them choose a different race and work with the player to swap out an equally powerful racial feature of the new ancestry for the Tiefling’s fire resistance.

Some players have a more sticky issue. Maybe there’s a new official character option they’re just dying to try out. Before you flat out say no, consider the impact of allowing them to play the character.

If they really want to try out an artificer in your low-magic campaign you can often say yes by clarifying the ups and downs of introducing that character to the campaign. They will be able to do magical things that most others cannot in the setting, which is a powerful bonus but they will also be hunted by people who want to use them or destroy them. The character may have to keep their magical abilities secretive to protect themselves and the rest of the group.

However, sometimes a player just isn’t able to provide a sufficient reason for wanting to play a character that doesn’t fit with the guidelines in the campaign primer. If they “just like playing elves,” that’s not a sufficient enough reason to accommodate the player. It’s OK to tell them no, the character doesn’t fit this specific campaign.

They can save the character concept for another game in the future, but for this campaign they need to create a player character that fits what’s outlined in the campaign primer.

Make Your Campaign Primer Easy to Access

Since this is the 21st century, you’ll probably be making your campaign primer using a computer and some form of text editing software. That’s great, it’s very easy to make it accessible to your players. You can send it by email, discord, or host on cloud storage like Google Drive and send them a link to access.

But, you should also consider printing hard copies of the campaign primer to share with your players. Digital access is very convenient, even at the table when you’re playing, but pulling out a phone or web browser to look it up can end with your players getting distracted by an email, text, or meme.

Your physical campaign primer can be as simple or elaborate as you like (or afford). A well-laid-out word document printed at home and stapled works great. Or, if you have the time, money, and design flare you can get a professionally printed booklet with full color art and saddle-stitch binding. These more elaborate campaign primers are great if you have a homebrew world you plan to run games in for years.

YouTuber and author Seth Skorkowsky goes an extra step beyond providing the campaign primer for his players. He also provides players with their own folders to make it easy to keep track of character sheets, handouts, primers, and session notes. Not a bad idea to stock up on folders when school supplies goes on sale. See below.

How to Start Your D&D Campaign Primer

We’ve covered a lot of ground talking about the purpose of a D&D campaign primer and how you can use it to full effect, but now let’s talk about what should go into your primer, the meat and potatoes.

Start with the elevator pitch for your campaign. Hopefully by this point you’ve already shared the campaign concept with your players and they’re on board. Dropping the elevator pitch right in the front of your campaign primer reiterates to the players what the campaign is about at a glance.

Point out what your world or setting is about and what makes it unique. Here are a few bullet points I put together to give you an idea of what you might want to emphasize.

- The Dread Lord is MIA and everyone with some power is scrambling to scavenge their pound of flesh from the empire’s corpse as it falls apart

- Powerful commanders are turning robber baron and carving the land into their private fiefdoms through intimidation and violence

- Soldiers and mercenaries now without a paycheck are becoming hired muscle, rogues, and adventurers

- You can also try to use a comparative statement that draws on works your players are already familiar with, “It’s like the movie Three Kings set in Mordor”

After that, you should include the specifics of the campaign you’re planning to run. These inclusions will help to answer some of the most common questions players have about a new campaign. What rules system are you planning to run? Are you using homebrew rules adjustments, is homebrew material acceptable for player characters?

Below are some of the most common questions you can answer for your players.

- Rules System, RAW or with homebrew adjustments?

- Where can players referene the homebrew do’s and don’ts?

- Genre & Tone (It can be helpful to provide reference examples a la Appendix N)

- Is the campaign serial or episodic in nature?

- Plot or Character-driven?

- What’s the expected level of lethality for player characters?

- Playstyle & Pillar Mix (Lots of tough tactical combat with miniatures & maps or mostly RP situations where ROLE PLAY trumps ROLL PLAY. How much exploration do you expect?

- Emphasis on Urban, Rural, Wilderness, Seaborne, or Planes-hopping?

- Scope & Stakes

- Expected start & finishing party levels

- Working for one small farming community or saving the world?

Primer Sections for Your D&D Campaign

With the preface and introduction to your campaign primer finished we can take a look at the different sections you may want to add for your D&D campaign primer. It’s important to remember when looking at the sections below that the aim of our campaign primer is to provide information that is relevant, useful, and concise.

Consider what information a player needs to bring a successful character to the table and to be capable of making informed decisions both in creating their PC and for acting as that character in the game world. Review the information after you write it all down. If the information doesn’t do that, be judicious with your editor scissors and cut all the fat you can.

D&D Campaign Primer Sections

- Character Creation Notes

- Starting Adventure

- Local Area Information

- Region Information

- International Affairs

- World Truths

- Cosmology

The primer sections are organized with an inside-out approach centered on the player characters. We start with what your players need to know for creating their characters, background for the starting adventure and the local area it’s set in. Then the information expands out to the local region, larger news and affairs of the nation states, truths about the world, and ends with the cosmology.

Done correctly, players should spend the majority of their time at the start of your primer. If this is an ongoing campaign they will begin to use information towards the middle and then potentially at the back of the primer.

Let’s get started with the Character Creation Notes!

Character Creation Notes

The first thing you want to include in the character creation notes for your D&D campaign primer is any house rules and other deviations you use from the rules as written. Let your players know this right off the bat before they start building a character using an incorrect method.

Next, you want to have a short list of Do’s and Don’ts for character creation. We want to address as many player questions up front as we can and leave as little confusion as possible. Here are the most common things you want to note for your players’ character creation:

- Player character starting level

- Ability score method

- ABCs allowed or restricted

- Ancestries, Heritages

- Backgrounds

- Classes, Subclasses

- What character-building materials are available

- Homebrew

- PHB only

- PHB+1 other official source

- Unearthed Arcana material

- Published setting guides

- How to run ideas by the DM for assistance and approval

- Your backstory expectations

- XGE’s This is Your Life

- Which other party member is your PC connected to and how?

- Why is your PC in the starting town and why do you personally care about the threat the starting adventure poses to it?

- If they’re not from the area, how did they wind up here?

- The Six Questions to Answer for the Ultimate PC Backstory

- Rules for starting gear, wealth, and magic items

- Note that the player’s PC requires approval from the GM before play

Another good section to include here is any special guidelines or rules you use for leveling up player characters. It’s not useful for character creation per say, but when your players are leveling up between sessions, this is likely the section they’re going to reference.

- XP tracking or milestone leveling?

- Can PCs level up trying to take a long rest in the dungeon or wilderness or do they need to be safe in town between adventures?

- How do they determine what hit points PCs receive at level up?

Starting Adventure

As players go through the process of character creation, especially as they think about their background and backstory, they’ll want to peek at the starting adventure to ensure they’re making a character that’s going to be useful starting out.

For example, you don’t want to make a social RP skilled-up bard for a starter dungeon full of mindless undead. Sure, the rest of the campaign you’re cooking up will have plenty of opportunities for a bard to shine, but it’s crucial for a campaign’s success that the players like their characters and they feel useful right out of the gate.

So focus on what your player’s need to know to help flesh out the PC and be prepared to hit the ground running in session one. I often just dump the party at the first session directly at the adventure location. We don’t need to waste an hour and a half in awkward tavern talk before accepting the initial quest. The PCs said yes, you’re outside the dungeon, what do you do?

You can always do a flashback scene in the middle of the session or the start of the second session once the players have some idea of who the characters are and their relationship. That will make the meeting in a tavern scene much smoother.

Goal & Motivations

The first information you want to note is what is the party’s goal. Make it simple, clean, and clear and provide them with motivation. The motivation can be material or personal. It could be straight cash, the rumor of a magic item, or maybe the promise of a paying job that will take them away from this backwater village.

Also be clear on the stakes of your D&D campaign primer’s initial adventure. What happens if they fail? If you’ve done your work in the character creation section they should have a personal stake in the starting area that is being threatened by the adventure’s failure.

Also include any timer or countdown for the adventure. If they need to retrieve a component for a life-saving medicine, make sure they have a concrete idea of how much time they have on the clock.

Expected Challenges

Going back to our bard example from above, resist the urge to keep the initial adventure a secret. The next session of D&D is the most important session of D&D and where your campaign primer is focused right now is the first session.

We want players to pick character options that make sense for the initial adventure so they can be set up to overcome the challenges. They can always retrain options later if the campaign moves in a different direction.

We want them ready to kick butt in session one, but you’re the DM. Just because they’re appropriately prepared doesn’t mean it’s going to be easy for them!

Adventuring House Rules

Make sure to include any house rules about adventuring you plan to use as part of the campaign. If you’re not interested in tracking resources (ammunition, encumbrance, rations, torches) let the players know.

Also, let them know if you’re going to use an alternative mechanic like resource dice, or if you are going to be a real stickler about resources because you want survival and running out of resources to be a major theme in your campaign.

Include anything where your DM style deviates from the most common denominator. If you don’t handwave travel or you’re big on random encounter chances, let players know. If every goblin, orc, and gnoll they meet will always be evil and a threat, let your players know so they don’t try to parlay.

If you can provide your players with this information about the starter adventure in your D&D campaign primer, they will not only feel rock solid about the characters they make, they’ll have clear expectations of the first one or more sessions of your campaign, which will give it a much higher chance of player interest, investment, and long-term success.

Local Area Information

Assuming you’re following D&D’s expected tiers of adventure and your campaign will fall into the most common bucket of campaign adventuring is spent between levels one and seven, the local area is a place with which your players will become very familiar.

Now, in most campaigns the PCs start in the childhood home of at least one of the party members if not most of them. So in your D&D campaign primer be sure to include information about the area. Because whether they were born there or just been in town for a while, the party should know quite a bit about the local area.

They will know things like notable NPCs, news, rumors, points of interest, etc. So, include that reference material for your players so they feel like they know the area and it will reduce the amount of in-game twenty questions you’ll need to play.

- Notable NPCs & Factions

- Known Goals & Commitments

- Threats & Opportunities

- News, Rumors & Points of Interest

- Creatures

- Events

- Places

- Things

You’ll notice here I didn’t say write any history about the local area. What’s going on now or at least recently, is far more interesting and impactful to the start of your campaign than when the town was founded and why.

You can include that historical tidbit, just make sure it’s relevant and useful for the players, e.g. Chekhov’s Gun. If the town was founded around a, now long-abandoned, mine, something better be going into or coming out of it in your starting adventure.

The information above not only helps your players feel like they understand the local area at the start of your campaign, it’s fertile ground for potential adventure hooks and sidequests. Make notes about the different local area information the players ask about or want to visit.

Region Information

From the local area we want to raise their knowledge of the D&D campaign setting by one level to information about the region they are occupying. Again, we’re focusing from the center out so you don’t need to stress the minutiae of the rest of your setting for the primer.

You want to focus on the basic information any basic character in the world would know about the region where they live. They would probably know who governs/rules them at the regional level and any other VIPs and factions at play.

The common person would probably know the capital, approximately where it is and even some of the more high-profile points of interest within and without. For instance, in addition to the region’s capital, a layperson could well know that there’s a minor baron’s keep a few days East from their location.

Remember, according to Wizards of the Coast’s own D&D research, most games focus on levels 1-7, so there’s plenty of time to expand on the details of the regional area as the party finishes adventures and grows in power.

Focus on including this information in your regional information:

- Ruler & Major Factions

- Capital

- Notable Locations & People

International Information

Zooming out one more level on your campaign setting you can provide some top-level information about the greater surrounding world. Depending on the scope of the campaign you are planning, this information will be of more or less importance which is why we don’t want to spend a lot of time on it.

But, this information can be very useful for players who are considering creating characters for your game that are not from the starting area. This section should provide them with the basic information they may need to get an idea of who their player character might be.

First, address some of the nearby factions to the starting area and the status of relations between these factions. Next, add some information about the neighboring people and their culture. It can help to focus specifically on how they are different or more “foreign” from the people and culture of the starting area.

Consider what ancestries and heritages are common to the land. How is their society organized, how are their classes/castes organized? Give a brief description of any notable customs and practices, holidays, rituals, and rites that are different to the starting area.

Additional information to include should be the people and their attitude towards adventurers, magic, outsiders. You may also include in recent or ongoing major events such as wars, disasters, or leadership changes.

World Truths

In this section we want to provide our D&D campaign primer with information about the world as a whole. What we want to avoid is writing an exhaustive history of everything that has happened since the world creation event. Focus instead on information that will be important to your players and their characters to know.

Add information about how old the world is. Is time circular and seen many ages rise and fall, making ancient ruins and lost technology sites that dot the landscape very common? Provide a brief timeline of world events that reinforce the campaign’s genre/tone.

Focus your attention on current events that serve as a backdrop to the campaign, such as an ongoing war or religious schism or reformation. Include any assumed knowledge, basic info anyone in the world would likely know.

Include the level of magic and technology of the world. Are magic cantrips and common items incredibly accessible and used in everyday life? Have people mapped the world and determined how to navigate the oceans precisely? Also consider any specific world truths that are specific to your setting. Do all creatures turn into undead after death unless cremated?

Cosmology

At the end of your homebrew D&D campaign setting information is the place to add any information about the setting cosmology. This section will be the least important for most players. The main players who will look through this section will be those playing divine classes that are looking for a god to worship.

You can even consider scrapping this section if you decide to use the basic D&D deities and planes, because your players will be familiar with those and have many resources they can reference if they have questions.

But, if you are creating your own homebrew planar cosmology go ahead and add a map of your planes with a description of each plane. Then do the same for deities. For most deities you only need a name, short description, and their relevant domains. Any player interested in playing a particularly devout character will approach you directly for more information if they have questions.

The last thing to add in this section is a calendar with the relevant dates, holidays, and observances. Because this is the most common page that may be referenced, you should consider making it the back page or insider cover of your homebrew D&D campaign primer, after the section on table etiquette.

End Your Primer with Table Etiquette

In a perfect world we wouldn’t need to worry about table etiquette. Unfortunately, we don’t live in a perfect world and if you’ve played tabletop RPGs for a while you have probably encountered one or more problem players at your table. Adding a section about table etiquette in your homebrew D&D campaign primer sets a clear expectation from the start about the behavior that is acceptable at your table.

Include the table rules and if you like an actual, written out, social contract. It may seem a little foolish to go so far, but right in your primer is really the very best possible place to include this information and have players read and be familiar with the expectations even before a Session Zero.

Talking about what you should include in table etiquette could be it’s own article and it has been extensively covered by people across the internet. But, to consider what you may want to include I suggest reviewing this page to start: https://rpgmuseum.fandom.com/wiki/Social_contract

Think about including subject matter warnings for themes you expect to pop up in your game (body horror, spiders, violence against children, etc.). Also discuss what safety tools are available for your players and should a player become uncomfortable how to bring it to your attention.

Consider adding in notes about the most common issues with gaming groups. What will you do if a player can’t make a session, does their character get experience? Is player vs. player antagonism OK or not, what about the rogue stealing from the party? Even something as mundane but prevalent as dice that fall off the table must be rerolled can be worth adding.

Make Your Campaign Primer Pop

Congratulations, if you have been working along as you read then the content for your campaign primer is nearly complete. You should have the bones of a wonderful resource that with some minor tweaking you can use for games you run for many years to come.

Now we want to talk about the presentation of your D&D campaign primer. Now, for good or ill, the more professional the presentation of your campaign primer the more likely it is to excite your players and be a resource they actually take a look at every once in a while. For artistic and desktop publishing wizards, you can really use your talents here to make your primer shine.

But, even if your art sensibilities lie in the realm of stick figures, you can still upgrade the presentation of your campaign primer. We’ll discuss how to make your homebrew campaign primer pop by focusing on three specific areas: Formatting, Visuals, and Style.

Formatting Your Primer

The key to great formatting is a strong hierarchy of information. Your primer may contain a lot of content, so you want to chop it up into bite-sized sections that make sense and flow in a natural order. That’s why we emphasized early on building the primer information from an inside out perspective so it would be in a useful order for our players. The idea is to make the information skimmable and easy to find.

Make liberal use of headings and subheads to emphasize at a glance what information is contained in the following paragraphs. Any standard word processing software can help you arrange and denote your sections until the primer feels right.

Now, nothing but paragraphs of information, the “wall of text” can be both intimidating and a bit boring to the average reader. Take this opportunity to review your primer’s content and look for ways to break up paragraphs using elements like bolded sections, lists, tables, quote blocks, and breakout sections. These elements can help you highlight the most important information in your primer and break up the amount of text on the page making it easier to read for your players.

You should also consider at this point whether you want a one-column or two-column layout. One column layouts are the best for long paragraphs of text, which is why it’s used for novels and text-dense materials like contracts. A two column layout is very useful for things such as reference material and types of writing that will be heavily broken up by tables, lists, graphics, and other breakout sections.

You’ll notice that most RPG rulebooks use a two-column layout. Flip through the pages of one or two and notice how often paragraphs are broken up by these visual elements. Now look at your primer’s content and decide which layout makes the most sense for the type of content you have.

Primer Visuals

Probably the best way to break up paragraphs of text in your D&D campaign primer is by including some nice visuals. Now, if you are creating a campaign primer for personal use at your table you can go and grab whatever art you think best represents the genre and tone of your campaign.

Look specifically for pieces that have both a subject and style that reinforce the tone of your setting. For instance, if you’re running a ‘20s/’30s themed horror campaign like Call of Cthulhu consider sticking to black and white line drawings with a heavy art deco emphasis and film noir style photography.

If you are interested in publishing your campaign primer for commercial use, you will be more limited in the type of art visuals you can use to supplement your primer. For starters, review art that is Creative Commons licensed and take a look at stock images. Though harder to find a cohesive tone to your visuals using this method, they can help you avoid legal issues in your publishing.

Another route is to commission original art to include in your published work, where you will be the sole license holder of the art. Commissioning original art, especially quality art, can get expensive quickly so you may want to consider this for the most high-impact pieces like cover illustrations.

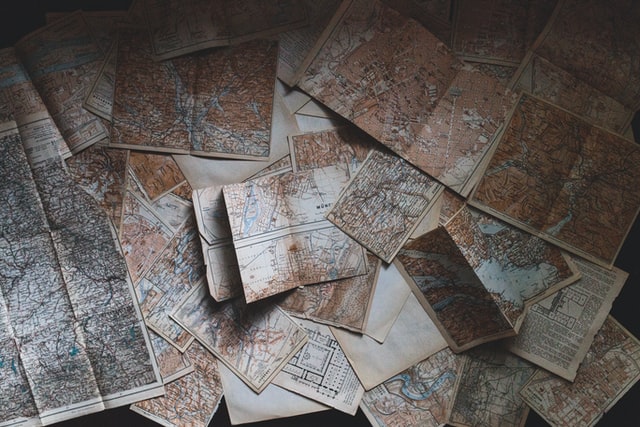

Another high-impact area to consider creating or commissioning art is maps.

Campaign Maps

People love maps. Hands down they are some of the best visuals to include in your campaign primer and if you are commissioning a piece, a nice artistic map is one of the top pieces you should consider.

Maps for your homebrew campaign primer pull double duty. In addition to being a nice visual element it grounds the locations in your setting’s world and provides players with a spatial reference to the people, places, and events you mention in your information about the world.

Now you may be ready to runoff and start work on a world map, but that can be jumping the gun. The suggestion is to follow the same inside-out structure we used for organizing our information. World maps are great, but a local map will be much more useful to your players. For an example we can look at D&D’s published properties.

Which do you think is more useful for DMs and players: a map of Faerun OR Curse of Strahd’s Barovia. Faerun is massive and whether you’re playing a published or homebrew campaign in the Forgotten Realms the adventure group is going to spend most of their early game sessions in one small, under-detailed area.

Whereas in Curse of Strahd the player characters are running back and forth across the map of Barovia to visit different locations and searching for the important things that will help them defeat Strahd. That’s because Barovia is tiny in comparison, player characters can cross the entire map in two days. But, it’s full of locations that are accessible and central to the current adventure.

So if you’re thinking of including maps in your campaign primer consider this descending order of what to include:

- Local Area Map

- Region Map

- World Map

- Cosmology Map

Campaign Primers with Style

When it comes to the aesthetics of a document of this nature you can break it up into two main sections: typography and visual elements. For an easy way to tackle both that follows the publishing style set out by WoTC’s 5e you can use the websites GM Binder and Homebrewery.

Both use a very similar in-browser editor using Markdown to create pages that look like they’re ripped from the official PHB or DMG. And, using the familiar visual style of 5e will lend a bit of professionalism and familiarity for the readers of your homebrew campaign primer.

Beyond those simple options you will start venturing into the sphere of Adobe InDesign and other desktop publishing suites. Now, if you’re familiar with those programs already it’s not a big deal, but they can be difficult and expensive learns for a DM creating a campaign setting they’re not intending to publish professionally.

If you are InDesign proficient, I encourage you to check out the subreddit R/UnearthedArcana. In addition to providing community resources for D&D official layout templates you can find many free resources to help you create polished and professional campaign primers that DON’T ape the style of D&D 5e’s official material. Perfect if you’re wanting to create a document for a different rules system.

Finishing Your D&D Primer

Now we come to the final steps of putting together the perfect homebrew D&D campaign primer. First, make life easy on yourself and keep a separate working draft of your campaign primer.

Doing so makes it very easy to open a copy of it for future campaigns and make changes while keeping the original template in pristine condition. This makes life very easy on subsequent campaign primers as you’re likely to use almost the same wording in many sections, especially if you’re running a new campaign in the same world setting.

Once you have your primer completed, check it for errors and add references in the form of URLs or books with page numbers. Give a final review of the content. Is everything in your primer relevant and useful for your players? Trim any fat you can because a shorter primer will always get more use than a hefty tome.

Now, let someone who’s not in your upcoming game read your primer and check it for understanding and errors. And, after presenting the final product to your players, be sure to make notes of any questions they have or sections that were unclear. Take that feedback and update your primer for future use.

Looking Ahead

Thank you to those patiently waiting for this one to come out. I went from being ahead of schedule to very much behind schedule due to work, health, and life issues. Needless to say, the last month has been a long one. I think I’m going to take an extra month to recover before hopping back into the world building series. Maybe I’ll do a review of Ex Novo, the collaborative city-building game I’ve been toying around with.

We’ll see you next time.