Welcome back, we’re continuing the discussion on upgrading your D&D game’s DC/TN. In the last section we created a way to make dynamic Difficulty Class/Target Numbers for your game. The focus was to create a system that gave you the flexibility to interpret results, reduce the pass/fail dichotomy of rolls, and collaborate with your players. All without increasing mental math to your cognitive load as DM. If you haven’t checked it out, you’ll want to read it before we get started on today’s topic.

Improving DC/TN in D&D, Dynamic Adjudication

So, last time was all about how to interpret roll results versus a DC/TN. Today, we’re tackling the DC itself. And we’re doing that by looking at three simple changes to DC/TNs for your game. The goal is to make them easy to create/improvise, make them fast and easy to run at the table, and introduce a different format for extended checks.

Fast & Easy DC/TN Creation

Longtime readers will know I have a fondness for the bell curve over flat probability. And that fondness extends to using 2d6 rolls to determine random elements for my game when possible. If you don’t run D&D – First off, hi! I’m not sure how you got to this article but thanks for stopping by – players are always coming out of left field with shenanigans you don’t expect. And that means you have to decide on a DC off the top of your head. And that can be difficult. Both, thinking of an appropriate number based off the plausibility of success measure against the character’s abilities and because some players believe setting a DC too high is done specifically so their cool idea will fail and they’ll have to play the game your way. Look, there are a lot of bad GMs out there who fall into the latter category. But, they’re not you, because you’re here learning to be a better Dungeon Master!

The YouTube video from Dungeon Craft below notes an additional benefit of rolling dice in the open. If you roll a random DC/TN in the open and the PC fails the blame is placed on the dice, not you as the DM. Just like with natural 20 monster attacks and saves. The dice giveth and taketh away, and their whim is fickle. The best part is using the 3d6 random roll framework below your players will still not know the DC. It’s in front of you, but not obvious. In the same way up-close sleight of hand magic operates.

3d6 Random DC/TNs

For this framework you roll 2d6 and 1d6 at the same time. The 2d6 are used on a table to set the DC/TN foundation. These numbers are ripped straight from the D&D 5e section on creating DCs. Most D&D DCs float in the 13-17 range so we want that to be the middle of our curve.

2d6 – Foundation DC

- 2 – Simple, DC 0

- 3-4 – Easy, DC 5

- 5-9 – Medium, DC 10

- 10-11 – Hard, DC 15

- 12 – Very Hard, DC 20

Add the remaining 1d6 result to the foundation. This makes most DCs float in the 11-16 range (avg 13.5). You might be thinking, that’s a little low. This is the normal range for General DC/TNs. These are checks that don’t require any special training to accomplish: notice, climb, most social DCs. If the character is attempting something that requires proficiency you double the 1d6 result. Making the normal range for specialty DCs, 12-22. That’s an average of 17.5. A combined average range of 13.5 – 17.5, right where we want to live. But, the framework offers us a wide, 1-30 range for DC/TNs.

Why Double the 1d6 for Specialty DC/TN?

PCs that attempt checks with required training already have a proficiency bonus to their roll. This is something I think the 5e designers really missed. WoTC’s DCs don’t appear to account for proficiency bonuses, much less expertise. That’s another reason for doubling the 1d6. Many character builds get expertise or default advantage on rolls. Enter the rogue that never seems to roll below 20 on Stealth and is functionally invisible outside of combat. And the last reason, I find it thematically appropriate that on average a task that requires specialty training to even attempt is more difficult than a general task. I believe it reinforces the idea of a complex or difficult task that cannot be easily accomplished through luck or brute force methods. Defusing a bomb is difficult, it should feel more difficult than smashing the bomb to pieces with a sledgehammer.

This framework is very easy. I run D&D without a DM screen and use it all the time by keeping 3d6 nearby. You can keep one die a different color for simplicity or do like I do. I use uniform dice and always read them left to right. I can roll in front of the players, say a number that’s not the dice sum and they don’t know how I came to the number. I can roll 3+6 and a 4 then say, “Give me a DC 18 Medicine check.” I admit, there’s a sadistic pleasure watching that one, incorrigible metagamer (you know the one) get frustrated because they don’t understand the numbers.

You can also use this method to pull the old Gary Gygax trick. I like rolling 3d6 while the players are distracted from the game and then make a nonsense note. Nothing regains table focus like the DM making a roll without saying anything.

I love the versatility of using 3d6 when my players try some risky, hare-brained scheme. I pick up 3d6 and roll them. Now if they succeed/fail it’s on the dice and not on me.

Room-Based DC/TNs

Runehammer‘s Index Card RPG is a great example of streamlined design. He also does some fun adventure design videos on his YouTube channel. One of ICRPG’s streamlined designs is Room DC/TNs. The idea is everything in a general area subscribes to one target number. Check for traps, TN 12. Move the boulder, TN 12. Save versus mold spores, TN 12. It keeps a Dungeon Master from diving into room descriptions or improvising DC/TNs every time the players interact with a part of the room. It shifts the focus from the dice mechanics of the situation to what’s actually happening in the narrative space. There’s a lot to like about it.

However, singular room DC/TNs break down for me in two places. The first is the specialized skill rolls I discussed above. We’ve already addresses those inherent problems. And number two, it doesn’t handle multi-round challenges. Anything that requires multiple checks, like a skill challenge. Which I find odd, because ICRPG actually has a mechanic for the latter issue. It’s just not included as part of the Room TN.

For me, one number can’t handle the situation with eloquence. I need something between one number and individual DC/TN for everything. To that end I turned one DC rooms into 3 DC rooms.

When creating adventures I use the following notation.

ROOM NAME X'Y'Z X = Basic TN Y = Specialty TN Z = Effort Multiplier

Example: Alchemist’s Atelier 12’14’3

Right in the the room title I have access to the fundamental numbers I need to run it. For me it’s the perfect middle ground. Upturn a table, TN 12. Identify potion ingredients, TN 14. Brew a potion, TN 42. Does 42 seem high? That’s because it’s Effort, the last upgrade we’re going to discuss for your game’s DC/TN.

Effort DC/TNs

Effort is another bit of streamlining lifted from the original concept in ICRPG. It covers two different scenarios.

- Any task that would require more effort or time than one person in one round can achieve. Think of it as a stripped down, free form riff on D&D fourth edition’s skill challenges.

- A failed single check you can expand into ‘failing forward’ and increase tension in the scene.

Effort & Consequence

A critical piece of RPG check mechanics, especially in regards to Effort, is consequence. You must have consequence for a failed check. Consider unlocking a car door with an analog key. Normally there’s no consequence for failure.

Drop the keys, try to put the key in upside down, have a gummy cylinder that’s difficult to turn. Minor annoyance sure, but you can just keep repeating the process until you unlock the door no worse for wear. Now imagine the same scenario in a horror movie.

With every stressful failure the masked killer gets closer, the probability of escape, slimmer. Stakes, consequence, tension. In old-school D&D that consequence was often the possibility of a wandering monster encounter. The more you screw around, the more likely you are to get into a fight.

Fights that drain your resources, increase your chance of death, and (because combat doesn’t drop XP in old-school D&D) don’t advance your character’s power. It’s the tax you pay for screwing around. Combat is typically a bad idea and smart, experience players look to avoid it whenever possible. Which, has a lot of gameplay benefits.

There may be a future blog on the benefit of wandering monsters. My thoughts about them has done a full about face once I understood the design intent. And given modern D&D and Pathfinder’s approach random encounters I don’t think they understand wandering monsters.Or at least, they don’t expect their customers do.

Creating Consequence for your DC/TNs

Why are you making the rogue roll to pick a locked door?

If they fail is there any consequence?

No? No roll necessary, the rogue unlocks the door. With ample time and capability the rogue will unlock the door.

Yes? The rogue needs to roll the attempt because if the rogue fails they get stabbed with a poison needle.

Once the poison needle happens the party can open the door without a check. The trap has accomplished its intent.

But, what if the tension was the time it takes to do the action. Any rogue can pick a lock given time and opportunity. A good rogue can do it quickly. Each failed attempt means something gets worse. The room fills up with water, Jason Voorhees gets a little closer.

The former is a trap and the latter, an unkillable enemy… which is a slow, recurring trap.

However, you don’t want your entire session to hinge on traps. If you adventure lacks a specific timer element, you can use wandering monsters. Prepare a small table of scenario-appropriate wandering monsters. Nothing elaborate, I find 1d6 works for me.

Every round the PCs make a check against the Effort DC/TN you roll 1d6. On a six or higher, a random encounter happens. For every safe roll, the subsequent 1d6 roll gets a +1 (Ex. 1d6, 1d6+1, 1d6+2, etc.). This guarantees a random encounter if the Effort DC/TN takes 6+ rounds to accomplish.

Examples of Using Effort

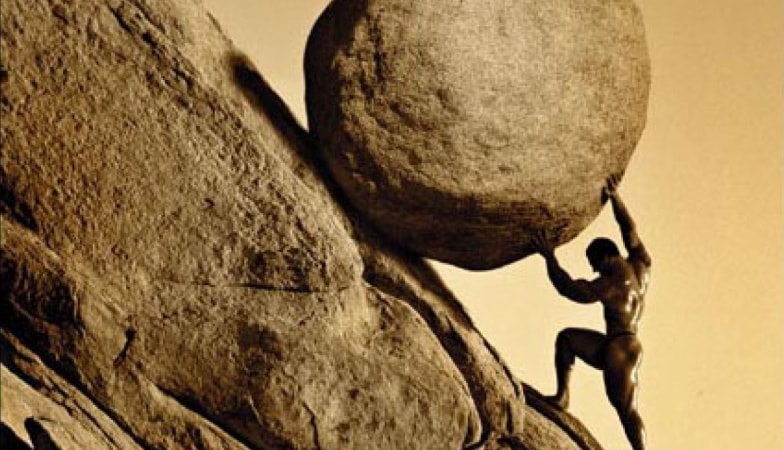

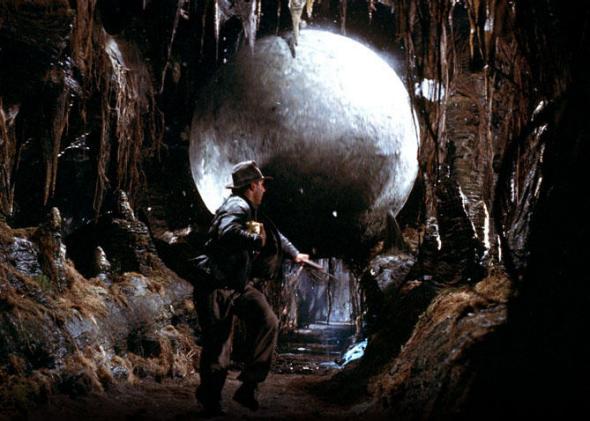

Scenario 1: Big Boulder Reset & Kobolds

The PCs have just avoided a “Raiders” style rolling boulder trap. Unfortunately the floor switch that opens the door is where the boulder used to rest. The PCs aren’t heavy enough to depress the switch. They need to reset the trap to do so. You can use Effort as the DC/TN they need to reach as a group to roll the boulder back into position. Each round they make one roll, adding any bonuses and enhancements they can to the single roll. You simply tally the roll totals to tell you how many rounds it takes to move the boulder back into position.

As a best practice, include some form of timer, some threat for the group if they’re slow. Sometimes this is a trap/trick/hazard, or each round it’s a roll on the wandering monster table. Or, you can have a specific timer. Like, kobolds attack in 1d4 rounds. But, if they fail to keep moving the boulder each round it rolls back down and they have to start over again.

Scenario 2: Poison Gas Whoopsie!

Dustin the Dexterous failed at disarming a DC 15 poison gas trap. Now the room is filling with poison gas. As a DM you take that DC/TN 15 and apply the effort multiplier. Let’s say the multiplier is four. Now Dustin needs to meet TN 60 to shut off the trap before the party succumbs to the gas. Each round the party must make a Constitution DC 10 save or take poison damage and begin suffocating. Because I’m a nice DM, Dustin’s failed Dexterity Thievery check of 12 counts towards the TN 60.

If you need to make an effort multiplier on the fly you can use the same 2d6 framework we used for creating random DC/TN foundations.

2 – Simple, x1

3-4 – Easy, x2

5-9 – Medium, x3

10-11 – Hard, x4

12 – Very Hard, x5

Aid Action, Experienced DM Variant

Rather than allowing the ‘Aid’ action, each PC that attempts to help the primary actor must make a check of their own. On a success the main PC gains advantage, on a failure the PC suffers disadvantage. Let PCs dog pile on disadvantage so long as they can provide a reasonable way they’re assisting. PC after PC make attempts to make a successful check to at least cancel out the disadvantage. Creating a wonderful situation where everyone just gets in the main PCs way with their “help”.

Putting It All Together

Let’s combine what we learned from this post and Part I. Starting with the Raiders-style builder door switch for this example.

Temple Entrance 15’20’3

The party have stolen the golden monkey idol and are ready to make their escape through the entrance, but the its sealed shut. The group makes a check, attempting to give advantage to the party’s best “Investigator.”

One PC casts Bless and one uses the Aid action (no variant). The rogue looks for the door release mechanism, Intelligence, Thievery DC 15. With a natural 19, bless, and expertise the rogue scores a whopping 28 on his check.

The rogue easily finds the large switch where the boulder used to rest. It needs something very heavy to depress it, much like the boulder that was originally on it. The strongest PC, the barbarian, takes point on rolling the boulder back into position.

Boulder Rolling: TN 45

1d4 Timer: on zero, 2d4 kobolds attack. Once defeated the timer restarts.

The DM rolls a 1 on the timer and the players groan. “You hear yips echoing through the passageway behind you, growing louder.”

Round 1

The barbarian takes the lead and braces against the boulder.

The cleric stands by and casts Bless on the barbarian.

The beefy dragon sorcerer muscles up next to the barbarian to give advantage.

The rogue slinks to the doorway and empties a bag of ball bearings.

The barbarian rolls high with advantage and adds the 1d4 from Bless to make it Strength 24 (24 of 45).

Five kobolds come rushing down the corridor and attempt a Dexterity DC/TN 15 save vs the ball bearings (I let the players use the room DC too!). Saves: 4 Failures, 1 Success (4,6,7,11,19)

Most of the kobolds scrabble and slam to the floor. One moves forward and jumps on the rogue with a dagger, but misses with an eight attack roll.

The rogue strikes back with a dirty 20 and jabs the dagger up under its rib cage, killing the kobold instantly.

Round 2

The barbarian takes the lead and braces against the boulder.

The cleric stands by and casts Bless on the barbarian.

The beefy dragon sorcerer moves to the doorway to Fire Bolt.

The rogue pulls out a hand crossbow.

Without advantage the barbarian struggles, but still manages a Strength 14 (38 of 45).

The sorcerer loses a natural 20 to disadvantage (prone target) but still smokes a kobold with Fire Bolt.

Even with disadvantage (prone target) the rogue scores a natural 17 and puts down the third kobold.

One kobold is able to stand up and deviously slings at the barbarian. The kobold gets advantage because the barbarian is fully busy with something else, but didn’t need it. Two Natural Twenties. Only five damage to the barbarian, but the shot hits right in the lower back AND the barbarian’s muscles start spasming. Make a DC 15 Strength save with Disadvantage or lose the boulder. The final result, 11.

The barbarian’s back seizes up and is unable to brace against the boulder. It rolls back down and slams into the wall with a loud crash. The final kobold tries to sling from the ground, but rolls a Natural One. Missing its target and instead slamming the bullet into the back of his celebrating compatriot’s head for three damage.

The party quickly finishes the remaining kobolds and starts the Boulder Rolling challenge again.

DC/TN EXAMPLE END

It’s so easy to create these cool and dynamic encounters from just a few numbers, even without rolling initiative. And it empowers the DM to make modifications as the situation dictates. Just like in the example, one lucky kobold sling attack changed the outcome of the encounter. It wasn’t a TPK, none of the PCs were badly hurt, but they absolutely failed the encounter and have to try again.

And allowing the room to dictate general DCs makes poisons, hazards, traps, and consumable items (ball bearings, tanglefoot bags, etc.) more useful in high DC rooms. They’re even likely to work in higher tier play. This is awesome if you want your combats to involve more hijinks.

This is the kind of fun, frantic game D&D and Pathfinder just don’t offer using the rules as written. So if you’re like me. The type of person who wants more in their game than roll a die, dictate success or failure. If you want combat to be more than two sacks of hit points whittling each other down. I suggest you try out these changes. It gives you the right amount of information versatility to adjudicate whatever the players throw at you, while making exploration simpler to run.

Thanks for stopping by. I really enjoyed getting these two blogs out of my head and onto the page. Retooling DC/TNs for me has been a gamechanger for me as a GM. Changing it from a sterilized order of operation of optimized moves into a chaotic mess of momentum and opportunity. And for me, that’s more how D&D should feel.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen players light up when combat is more than I hit you and then you hit me. Or seeing a simple task go sideways, get cranked up to 11, and the PCs scraping just to get out alive. And if you like this you may like my PWYW titles on DriveThruRPG. Or, if you want to support the blog directly, you can grab me a Ko-fi, and keep the RPG goodness flowing your way.

Looking for more content? Check out the worldbuilding project I’ve been working on step by step.